Words and Photographs By: Clare Buchanan

“I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin, I can get to the heart of all the cities in the world. In the particular is contained the universal.” – James Joyce

I arrived in Dublin off a train from Belfast.

I’ve wanted to come to Ireland ever since I was a wean, craving the green, craving the old country. I like to think I got my knack for storytelling from my Irish ancestors, the Tierneys, who emigrated likely due to the famine and found solace on the dark prairies of North Dakota. That Irish melancholy, I have it. My tendency to tell a story without ever really reaching the point, yes, that plagues me as well. I always knew coming to Ireland would be a pilgrimage of sorts, I just didn’t realize the extent to which this city would leave its mark on me.

I am permanently branded.

They love a good James in Dublin. James Joyce, James Connolly. Statue of Joyce on Talbot Road, overlooking the LAUS station, statue of Connolly in the park, overlooking a fountain. I, too, enjoy a good James. Joyce is one of my favourite literary figures. I think The Dubliners might be one of the single most important pieces of literature I’ve ever encountered. Similar to Joyce, I also want to write an exposing and extremely detailed narrative of my experience growing up in a city I have a tumultuous relationship with, not bothering to change the names of people and places I dealt with. I appreciate Joyce’s pettiness, but also his particularness in The Dubliners.

In Dublin, it’s impossible to not think about writing. Everything exists to invoke a sense of dire creativity within its inhabitants. There is no point getting up in the morning unless you plan to take a dreary stroll along the cobblestone roads of the city, smoking a slouched cigarette in the rain, contemplating the meaning of life. You cannot be a Dubliner and not be a thinker. The city will chew you up, spit you out, and send you back to England, where thinking is not a prerequisite to living.

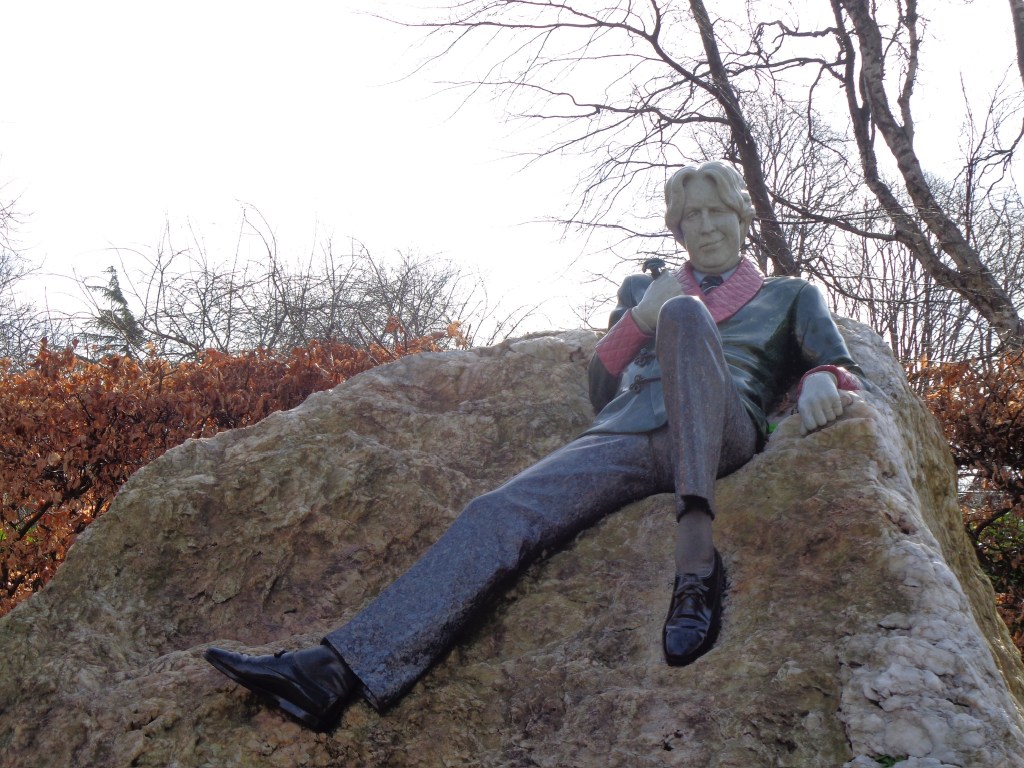

I have never seen a city have so many bookstores, both corporate and independent. Somehow, the two seem to coexist in Dublin. And one cannot forget the casual implementation of statues of literary greats scattered on every street corner, park square, and city center. There seem to be thousands of Joyce, and one cannot pass by Merrion Square Park without catching a glimpse of Oscar Wilde lounging on a rock like a lioness awaiting a mate. At the Museum of Literature, Samuel Beckett’s telephone has been encased in glass, a holy relic.

The Irish are very proud of their own, and in every bookstore there will be a section dedicated solely to Irish writers at the front of the shop. If for some strange reason you wish to find a book by an English author, you’ll have to tuck your tail between your legs, approach the counter, head lowered, defeated, and ask the shopkeeper where to find it, in which you will likely be told to make your way down to the cellar or the back corner of the store.

The beehive of intellectual society seems to congregate at the epicenter of Dublin: Trinity College. Trinity is the only college campus I have visited that is older than my beloved Salem College. Founded in 1592, literary giants such as Johnathan Swift and Bram Stoker attended here. Sally Rooney, author of Normal People and a literary giant on her own, also went to Trinity. My days in Dublin were oddly warm and sunny, and Trinity students bathed in the square, the first few buttons of their collared shirts undone, their eyelids flickering with pleasure at the rare warmth.

“If one could only teach the English how to talk and the Irish how to listen, society would be quite civilized.” – Oscar Wilde

I find myself in Dublin on Wednesday, March 5th.

I wake up early, in my hostel cubby, disoriented, realizing I haven’t slept in my own bed for a long time. I lay on the thin, scratchy linen sheets, the rising sun blocked out by the curtains around me, and try to think what bed I would even begin to consider my own. Would it be the one back in Grantham, at Harlaxton Manor, where I have been studying abroad for the past three months? Would it be the one in 1772 Hall, a bed in a dorm I have since moved out of? I wouldn’t consider the bed in my childhood bedroom in Los Angeles to be my own, I haven’t slept in it for two years.

I spend about five minutes thinking about the lack of grounding I seem to have before getting up to brush my teeth. I wake up early so I can take a few moments in the communal bathroom to enjoy my solitude, talking to myself in hushed tones like a crazy case, soaking up these last few moments alone. I spit toothpaste into the grimy sink and wash my face quickly as I hear my hostel mates emerging from their holes.

My travel mates and I head down to breakfast and fill our stomachs with food for the day’s journey, which will entail every museum we can possibly get into for free. We eat dried out pancakes and drink bitter coffee as we sit at a tiny table next to a group of four German men who speak in Duetsch I can slightly understand, Deutsch that reminds me of my late grandmother.

We are museum pilgrims, the type of American college students who don’t really come to Dublin to go to the Guinness storehouse, but instead to see the old things encased in glass at the National Gallery and Libraries and Guildhalls. At the archaeological museum, I stare at the corpse of a man who is estimated to have been alive around 430 BC, and has since been preserved in the bogs of Galway. I stare at the man’s caramelized body, his twisted and bare limbs, and have trouble assigning a soul and a life to this formation. I stare at the dirt under the dead man’s fingernails under the weird warm light of the museum and feel sick- like an alien in a strange society where dead people are showcased behind glass for visitors to come and observe. But then I get excited thinking about the fact that life does eventually come to an end, feeling immediately guilty after thinking such a horrendous thing, removing myself from the exhibit to take a deep breath outside of the crisp Dublin air.

After escaping the archaeological museum, I walk down College Street to Kilkenny’s Cafe and see countless individuals pass by me, a curious design on their forehead. I see the black ash crosses and feel an overwhelming sense of yearning. Ash Wednesday. I am in Dublin on Ash Wednesday.

As someone who grew up Catholic, this is a very big deal. For starters, Ash Wednesday was my favorite holiday when I was younger. As a child who often sought attention in the wrong places, I looked forward to Ash Wednesday because it was the day I’d get an ash cross drawn on my forehead that I then got to wear around school for other people to look at. It was all very self-oriented, my desire to be marked on Ash Wednesday.

I found the ritual of it, the marking, to be extremely dramatic and theatrical. I recall being an altar server, dressed in my white robe and violet cincture, assembling the ash together in golden, ornate basins behind the church for the priest to use in mass. The ash in my hands was often leftover from the palms that were burned on last year’s Palm Sunday. Catholics are very resourceful. Catholics are very clever. On a good year, the priest would draw a huge cross that was very dark and noticeable on my forehead. Sometimes the cross would be so massive the bottom would extend towards the bridge of my nose. On not so good years, the priest would give me a quick dash, barely noticeable, as if he had somewhere else better to be. The flamboyance of the cross would often vary given the priest. You can find out a lot about a priest based on his stylistic choices when marking one’s forehead on Ash Wednesday.

On our last night in Dublin, my travel mates took two hours to decide where to eat for dinner while I hoped for a quick and painless death, anything to escape the cycle of indecisiveness that seemed to plague my group.

We gather on Fownes Street somewhere near Temple District as two unspoken yet naturally assigned leaders of the group stand crouched over their phones, searching google maps for a restaurant that will satisfy everyone’s needs: a restaurant in Dublin, Ireland that isn’t a pub and also somehow simultaneously sells sushi, crepes, and burgers. I realize this feat will be impossible, and try to voice this reality- but am ignored. God forbid we listen to a voice of reason.

The joys of traveling with a group are that you are never alone. The horrors and atrocities of traveling with a group are that you are never alone.

I plead that we at least just find a restaurant where the cheapest thing on the menu isn’t 25 euros and sit defeated on the street curb, inhaling cigarette smoke and the alluring odors of emerging Dublin nightlife. If I had more energy, I would have left to go somewhere on my own. And while I knew it would be rude to just get up and walk away, I also knew I wouldn’t see these people ever again in two months, so I wasn’t too concerned about coming off as a jackass. But, I had this strange feeling that told me to stick around, to just give it a few more minutes.

At 6:45pm, a girl from our travel group texts one of the naturally assigned leaders and says that she met someone on her bus tour of the Irish coast earlier that morning and has invited them to eat dinner with us. We all laugh because now it will actually be impossible to find a table for eight people at a restaurant in the middle of Dublin nearing 7pm.

Around 7:30pm, we decide on a Mexican restaurant and wait outside for the rest of the group to arrive. One of my friends has to urgently use the bathroom, and I need some time away from the group, so we go across the street to The Hairy Lemon to sneakily use the loo. When we return to the street from the pub, the group has united, waiting for us. My gaze hovers over everyone I recognize, accounting for familiar faces and voices. In the corner of my eye, I notice someone unfamiliar.

My inner monologue begins to unravel: “Must be the friend of a friend that was met on a bus tour of the Irish coast. Dear God, she’s beautiful. Tall. Dark hair. Hazel eyes. Camo pants. Is that a tattoo I see? 1970s shag. Perfect. No – look away. Be normal. Wait, is she looking at me? Oh my god, she’s looking at me. Holy shit. Holy shit. She’s still looking at me. Okay, be normal. Be cool.”

The Mexican restaurant informs us we’d have to wait an hour for a table so we go across the street and wait in line for slices of pizza being shoved out a tiny hole in the wall reminiscent of a Dairy Queen drive thru window. Two hours of back and forth on which high end restaurant to go to- and now we’re sitting on the dirty curb with slices of greasy pizza in our laps. Typical.

I am so exhausted and overwhelmed I go mute, eating my pizza like a goblin in the corner. The beautiful, mystery person who was invited to dinner sits next to me, observing the conversations happening around us. When the group gets up to leave, we linger near each other, not saying anything. I stand so still and straight I fear my knees will lock and I will pass out.

One of my friends strikes up a conversation with the tall, mystical being and I very slyly enter myself into the conversation. I am natural, graceful, and poised, of course. We start talking. She’s from Kentucky. On a solo trip. (That’s interesting.) She’ll be in London Sunday. (I’ll be in London on Sunday.) She laughs at my jokes. I laugh at her’s, because she’s actually funny. We talk about Ethel Cain and Fleabag and Sally Rooney and we find out we’re staying at the same hostel that night and then I realize maybe I wouldn’t rather be dead, underneath the bog, caramelized, and drained of my juices. Maybe life is worth living- because I’m in Dublin on Ash Wednesday and there’s an alluring, androgynous person from Kentucky standing right in front of me. It’s only 8pm. The night is young, and so am I.

It’s uncertain who I’ll be when dawn breaks in Dublin, but I know that whoever she is, she’s someone I want to meet.

Leave a comment