Words and Photographs By: Clare Buchanan

Tiocfaidh ár lá.

Our day will come.

…

March came suddenly.

After two months of feeling like I was in a standstill, trapped in the East Midlands of England, nursing the sores of my past in the empty, grandiose halls of a Jacobean manor, I found myself clinging onto the intriguing possibility of spring break. I craved the chance to finally be on the road again, exploring the seedy and controversial bits of this foreign country I had found myself in that didn’t really feel foreign, rather an older but just as divided version of the country I call home.

While classmates flocked to warmer countries farther South like Spain, Morocco, Portugal, Greece, and Italy, I found myself having visions of stoic, brick, post-war buildings in a region of the world often overlooked: Northern Ireland. Or Ireland. Depends on how you choose to look at it.

Spring Break in Belfast.

This seems like an oxymoron. It’s almost disrespectful in a way.

About forty years ago, the mere thought of taking a weekend to vacation in Belfast would be incomprehensible. About forty years ago, I would have gotten looks of grave concern if I had said I was taking a holiday in Belfast. Forty years ago, Belfast was in the middle of a war. A war that has its origins when Ireland was first invaded, a time so long ago no one can really remember when it first started. It’s just always been this way.

Fredierich Engels once wrote in a letter to Karl Marx that “Ireland may be regarded as the first English colony.” And it’s true in a way, the global escapades of the British Empire would be taken for a trial run across the sea in Ireland. And while slowly, over time, the British commonwealth has disintegrated, the British occupation of Ireland has remained.

Here is a brief and understated generalization of the history of Ireland:

1169. This was the year the English occupation of Ireland truly began. However, the origin of English/Irish relations go back 2.6 million years, when an ice sheet separating what is today Ireland and what is today Great Britain melted, forming the Irish Sea.

1594. English Protestants have settled in Ulster in the Northern part of Ireland. Irish Catholics are forced into submission through the scorching of Irish villages and starvation.

1641. The Dispositions. The Irish Catholics rebel. One hundred English Protestants (men, women, and children) are stripped of their clothes, placed in a barn overnight, and then thrown into the freezing river the next morning. Catholics like to make a statement.

1649. Oliver Cromwell releases a reign of terror onto the island to seek revenge for the lives taken during The Dispositions. Irish people are displaced from their lands and some are sent across the Atlantic as indentured servants. Anti-Catholic rhetoric runs rampant.

1845. The Famine. 1 million Irish people die from starvation as Ireland is stripped of her natural resources and her people are used for cheap labour, all as England flourishes in all its sickly glory, wealthy with luxuries produced by the riches of Irish soil. Millions emigrate to America for a better life.

1897. Oscar Wilde, Dublin native and poet, is released from prison and moves to Paris after being charged with “gross indecency.”

1914. James Connolly, Ireland’s Messiah, calls for freedom and independence. James had excellent opinions on the role of the Irish people in global society, as well as an excellent mustache.

1916. Easter Rising. Dublin. 2,500 Irish rebels. 20,000 British troops deployed over six days. 400 dead, mostly civilians. 2,000 wounded. 3,000 Irish people who are suspected to have been involved are arrested. 15 Irish leaders are given quick trials before being executed by firing squad. James Connolly was the last to be killed.

1919. The Irish Republican Army, or IRA, is formed.

1922. Ireland wins independence as a “Thank you for all you did during the Great War!” Parts of Ulster remain under control of the United Kingdom. This region is termed “Northern Ireland” as if the real Ireland does not exist there, but rather below it. James Joyce also publishes Ulysses this year.

1969. The beginning of “The Troubles.” The IRA bombs Belfast and cities all over the United Kingdom to make a political statement. A “Peace Wall” is built separating the low income Irish Catholic minority neighborhood in Belfast from the neighboring English Protestant community. This is what some would call segregation. Irish Catholics are discriminated against and kept intimidated by a forceful, mainly Protestant police force. During times of resistance, Irish Catholic homes are raided and elderly people are dragged into the street, beaten, and shot at. And for what? For what? All for the idea of a so-called “Commonwealth” that died with Queen Victoria?

1972. Bloody Sunday. 26 unarmed Irish civilians are massacred by British soldiers during a protest march in Derry. The cobblestones are stained with blood. A priest waves a crimson stained white flag in the streets, carrying a wounded protestor to safety. The bombing and the raiding continue.

1998. The Good Friday Agreement. A step towards peace, towards the future. No more fighting. No more bombing. 3,500 lives lost in thirty years. A piece of paper puts an end to it. All that remained was an open border and two separate nations that were being forced to coexist after being in constant struggle with one another for the past 800 years.

…

“And if there ever is gonna be healing,

There has to be remembering.

And then grieving.

So that there can then be forgiving.

There has to be knowledge.

And understanding.”

- “Famine”, Sinéad O’Connor (1994)

…

Belfast’s air is thick with tension.

You might not feel it in the city center as you watch tourists line up single file into a red double decker “hop on-hop off” bus between the Pret A Manger and Gregg’s, holding sausage rolls and steaming cups of coffee as they await their ride. You might not feel it in the Victoria Shopping Mall in one of the department stores that sells plastic clothing produced cheaply for the masses whose playlists are more suitable for a rave than the inside of a shop at 2pm on a Monday. You might not notice the heaviness of the air outside of Queen’s University as you take a moment to sniff the daffodils and jonquils that have sprung up from dark brown beds of soil along the sidewalk. You won’t even think about the past, what was and has been and will be, at a gelato shop along the River Lagan, enjoying the cool taste of rosemary and sage cream on your tongue.

But if you walk about thirty minutes West of the Cathedral Quarter, you’ll find a section of the city that seems to be frozen in time. Murals are plastered on garden walls and sides of brick houses, in solidarity with Palestine and the European Union, in opposition to the United Kingdom and the United States of America. The murals lead you into sections of the city reserved to mourn the dead, gravesites from The Troubles, memories from a more violent time forty years ago. The Peace Wall still remains, a five minute walk from the Bobby Sands memorial mural that reads, “Our revenge will be the laughter of our children.”

Three children with bright red, curly hair chase each other around a power generator that has been suspended next to the Peace Wall, giggling with glee. But if you walk up to the wall, and run your hand over the dense, freezing cement, your fingers will find conclaves in the stone where bullets were once fired. Their intrusions remain.

It’s nearing midnight at Weatherspoons in downtown Belfast. I sit, fully sober, surrounded by a bunch of tipsy American college students sipping on Hooch and smoking messily hand rolled cigarettes. I was taken there by friends who were meeting their friends who were studying in Belfast for the semester. I’m happy to be included but am quickly reminded how bizarre it is to be the only sober person in a group of American students who can’t handle themselves after a pint of Guinness.

“And if someone asks you if you’re Catholic or Protestant- just say you’re American.” A friend of a friend, clearly drunk at this point, slurs her words as she speaks to me. Her septum is twisted all up into her nose. Her friend besides her has bright red dyed hair, a belly button piercing, and has been shooting daggers at me the whole night. She blows her vape smoke in my face and I find myself to be beyond exasperation.

“Well, I think I’d probably just tell them I’m Catholic.” I tell the drunk girl, my eyes not on her but rather at the string of lights hanging around the outdoor patio we were standing on.

“No! No!” The drunk girl has curly blonde hair and it’s sticking to her sweaty forehead. She has a lighter in her jean jacket’s front pocket with the Union Jack on it and is appalled by my initial answer. “See, you can’t do that! It will upset them.”

I scoff at this stupid girl. “I don’t really care.”

…

I have been fascinated with punk culture since I was fifteen and taped a copy of the Riot Grrrl manifesto on my bathroom mirror. Punk is a genre. The term is limiting and also all encompassing. Similar to the concept of ‘brat’, punk can be a verb, adjective, even a noun. Punk is a mindset. It’s a movement. I dated a girl from Greensboro who used the word punk to describe herself. She was covered in American Traditionalist tattoos. I distinctly remember she had a giant septum, gauges in both earlobes, and a horse with three heads permanently inked into the skin of her chest. She listened to bands with small followings on Soundcloud with obscure names that when played for me in her 2009 Nissan Altima sounded like someone was running their nails down a chalkboard while simultaneously slaughtering a litter of screeching piglets.

Many claim to be punk. Few actually are.

Sometimes being so anti-establishment, and so unconventional, creates an establishment that becomes a convention.

While watching a short film at the Irish Rock ‘n’ Roll Museum in Dublin, I found something that was said about the punk movement to be especially moving:

“New York had the hair. London had the trousers. Northern Ireland had the reason.”

Northern Ireland had the reason.

The spirit of Belfast still exists in the blue eyes of a woman who runs a grassroots museum about the history of the Irish Republic out of the back of a warehouse deep in the Catholic community of Belfast. She has a thick accent and immediately asks me where I’m from as soon as I walk in. I tell her I’m from North Carolina and she raises her eyebrows at me quizzically before having me diligently sign her guest book. She stands beside me, very close, watching me write my name in dark ink.

“Clare.” She says it matter-of-factly and I nervously laugh, then nod.

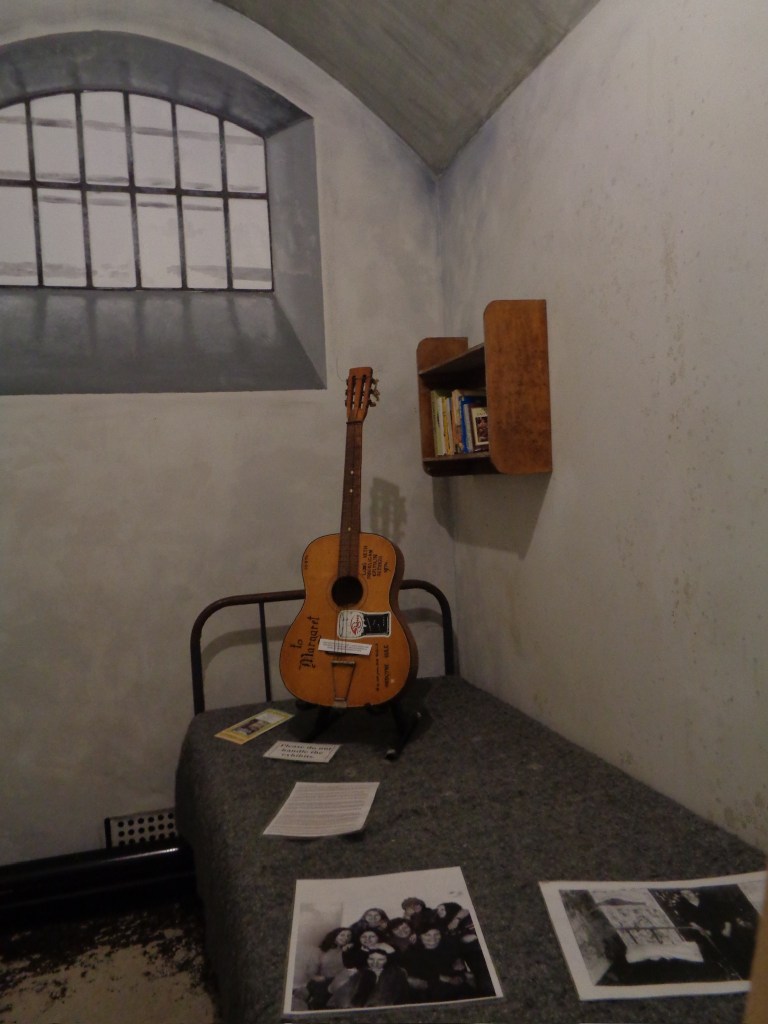

She doesn’t say anything else, just turns on her heel and heads into the depths of the museum, into a recreated exhibit of a women’s jail cell. When I don’t follow her immediately, she turns and gives me a scathing look.

“Oh, yes. I’m coming.” I say, desperate for her approval already even though I have just met her. I know she has stories to tell, and whether or not I am prepared to hear them, she is going to tell me.

She proceeds to lead me through each exhibit, which have all been cultivated by local Catholics over the years: pieces of fabric off a protest flag, IRA pins, IRA flyers, newspaper clippings, Bibles, crucifixes, anything to bring memory to the atrocities that happened not too long ago outside the walls of the very warehouse we were standing in.

We stand quietly in front of a picture of a group of women in a jail cell that has been printed out and placed at the edge of the mock prison bed. The girls are positioned in rows, the girls behind holding the girls in front of them, their arms around their shoulders protectively. Their expressions shock me. They are not afraid, they are holding each other, secure and smiling. I think to myself that a similar picture exists somewhere of my friends and I back home in North Carolina, except none of us have risked our lives to be political prisoners for the freedom of our country. (At least, not yet!) I feel an overwhelming sense of melancholy and emotion that I can’t place. I don’t say anything. I wait for the woman to say something. I don’t even dare to breathe.

The woman stretches out a papery white, thin, wrinkled hand. Her veins bulge out of her hand like mountain ranges, shades of blue and green, beautiful in their intricate and delicate form underneath her pale skin. Her hands remind me of my late grandmother. I want to tell her, but I don’t. The tip of her pointer finger lands on the face of a dark haired girl looking directly into the camera.

“This was my sister. She was arrested in 1971.”

I nod quietly, in astonishment. I look into her light blue eyes, a similar color to my own, and see a deep pain I’ve come to recognize during my time in Belfast. It’s a pain not marked solely by loss. It’s a pain marked by rage.

But the woman doesn’t dwell on it for too long. She doesn’t tell me what happened to her sister in the end, if her sister made it out of jail. She moves onward, motioning for me to keep up. “Come, let me show you the camera that was smuggled in to take these photos.”

She disappears behind a mannequin dressed in a balaclava, her long black hair trailing behind her like a cape.

And I follow.

Leave a comment